Mandatory Sustainability Reporting: Are you ready for 1 July 2024?

A re-cap of the keynote presented by John Vagenas at the AusIMM Tech Talk event

The Australian mining and minerals industry is entering a new era of sustainability reporting and climate disclosure requirements. Rigorous new Australian legislation is coming into force from 1 July 2024.

In October 2023, the Australian Accounting Standards Board (AASB) released its Exposure Draft ED SR1 Australian Sustainability Reporting Standards – Disclosure of Climate-related Financial Information. These standards are internationally aligned to the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) standards (both IFRS S1 and IFRS S2) and represent the biggest change to corporate reporting in Australia in decades.

What’s also significant to note is that the AASB is proposing to apply the standards to annual reporting periods beginning on or after 1 July 2024. This is very soon – and very important.

Driven by the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB), leading European Union (EU) bodies, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), and the National Greenhouse and Energy Reporting (NGER) administering the Safeguard Mechanism in Australia, these new standards will require disclosures on sustainability indicators such as GHG emissions across Scopes 1, 2 and 3, as well as water, energy, air quality, waste, hazardous materials, pollutants, nature-related risk factors, Product Carbon Footprint (PCF), Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) and TNFD impacts.

This is a far more comprehensive and in-depth level of reporting than any time in history.

All of this means that sustainability reporting is now elevating to be on equal footing with financial reporting in terms of accountability and significance. With the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) already cracking down on greenwashing with strong civil penalties, shareholder activists demanding action by boards, and share prices and capital markets hinging on ESG credit ratings, the time to prepare is now.

Following is a summary of John’s keynote at the AusIMM Tech Talk, and some of the insights he shared about this topic.

Contents

- Mandatory Sustainability Reporting: Are you ready for 1 July 2024?

- What is happening internationally?

- Overarching themes across all networks

- Scope 1,2 and 3 in the context of mining and minerals

- So, is sustainability reporting really that difficult?

- Scope 3 doesn’t have to http://be as difficult as people think

- The case for modern, digital tools for sustainability reporting

Why is sustainability reporting so important?

For engineers, reporting is not something new—nor is in-depth data modelling and analysis. In fact, John began his presentation by saying that he finds criticism of many organisations’ reporting capabilities (and the assertion that they must “do more” or “do better”) abrasive—especially when engineers have been working tirelessly (and often for generations) to pull together data on an organisation’s performance or adherence with requirements.

However, John also points out we are now in a situation where the scope of the requirements is so complex and multi-faceted, many engineers simply don’t have the digital tools—nor the capacity—to pull together the level of required data.

This is a very problematic situation for many organisations, especially those which are classified as major emitters – many of which also currently produce the resources upon which we all depend for our quality of life.

This situation is exacerbated by the assumption that forcing these companies to dramatically reduce their emissions by implementing levies and offset penalties will solve the problem. In fact, it’s much broader and more complicated than this.

Here in Australia, we now have new regulations set by the Clean Energy Regulator (CER) and its National Greenhouse Energy Reporting Scheme (NGER). As an extension of the NGER, the Australian Government introduced safeguard mechanism reforms last year.

These safeguard mechanism reforms require 215 of Australia’s largest emitters to reduce their emissions by 4.9% annually.

The problem is that the majority of these emissions are difficult to abate. This means that from an engineering point of view, there is actually very little organisations can do to reduce them – which forces them into a situation where they have to buy offsets.

So, how much would this cost? If we use the emissions numbers reported last year, and the government’s stipulated cost capped at $75 per tonne, it amounts to AU$29 billion per year for scope 1 and scope 2 emissions alone.

If we include scope 3, which eventually organisations will have to do, we will get close to $180 billion a year in offsets.

Under this sort of regime, there is no chance anyone could be profitable.

To add to this, the government is also proposing a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism, which aims to penalise imports based on their carbon intensity. So unless we have the capacity to produce resources ourselves, we just end up paying even more.

This is why organisations need to capture, measure and share their data – because we all have a lot to lose if we get it wrong.

We need to find a way to reduce emissions without financially crippling those companies, and without society slipping into energy poverty. Measuring emissions using powerful, digital tools—and using technology to identify areas for improvement—is absolutely crucial in enabling this.

What is happening in Australia?

Australian Accounting Standards Board (AASB) standards

As mentioned above, the new standards from the AASB represent the biggest change to corporate reporting in Australia in decades. Some entities (defined as “group 1” under the standards) will need to start reporting from 1 July 2024. Earlier this year, Treasury released its final Climate-related financial disclosure exposure draft legislation. The proposed legislation will require entities in scope to disclose their climate-related plans, financial risks and opportunities, in accordance with the Australian Sustainability Reporting Standards made by the AASB.

Safeguard Mechanism and National Greenhouse Energy Reporting (NGER)

Set by the Australian Government, this “mechanism” has existed since 2016—however it was recently amended in line with Australia’s climate targets. It requires the highest greenhouse gas-emitting facilities in Australia to keep their emissions below a set baseline. Organisations that fail to do so may face penalties.

Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM)

This is a new tariff applied to a range of carbon intensive products that are imported by the European Union (EU). The CBAM puts a price on carbon intensive products as they enter the EU. It considers direct emissions (scope 1), as well as indirect electricity and other indirect emissions (scope 2 and recently, some scope 3). As part of CBAM, EU organisations will ask Australian resource company exporters to provide details on the carbon emissions embedded in goods scheduled for import.

Importantly, the Australian Government has released a statement indicating it is considering the option of implementing a system similar to the EU’s CBAM. This would mean applying a tariff on carbon-intensive goods coming into Australia.

Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) This is a new tariff applied to a range of carbon intensive products that are imported by the European Union (EU). The CBAM puts a price on carbon intensive products as they enter the EU. It considers direct emissions (scope 1), as well as indirect electricity and other indirect emissions (scope 2 and recently, some scope 3). As part of CBAM, EU organisations will ask Australian resource company exporters to provide details on the carbon emissions embedded in goods scheduled for import. Importantly, the Australian Government has released a statement indicating it is considering the option of implementing a system similar to the EU’s CBAM. This would mean applying a tariff on carbon-intensive goods coming into Australia.

What is happening internationally?

For organisations that operate internationally, as the table below demonstrates, things are even more complicated. Companies need to meet obligations in Australia, as well as ensure they are providing data to international customers that also need to report under a different framework.

| Frameworks |  International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) IFRS S1 and IFRS S2 |  Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) ESRS 1, ESRS 2, ESRS E1- E5, ESRS S1 – S4, ESRS G1 |  US Securities Stock Exchange (SEC) Proposed rule, amendments under the Securities Act of 1933 |

| Geographic reach |

|

|

|

| Effective date | 1 January 2024 Adopted by the jurisdiction | 1 January 2024 Sector specific standards delayed to 2026 | Waiting – set to formally announce rules in 2024 |

Framework |

Geographic reach

|

Effective date 1 January 2024 |

Framework Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) ESRS 1, ESRS 2, ESRS E1- E5, ESRS S1 – S4, ESRS G1 |

Geographic reach

|

Effective date 1 January 2024 |

Framework US Securities Stock Exchange (SEC) Proposed rule, amendments under the Securities Act of 1933 |

Geographic reach

|

| Effective date 1 January 2024 Waiting – set to formally announce rules in 2024 |

Figure 1: Status of international sustainability frameworks

Overarching themes across all networks

Increasing complexity of disclosures

Organisations are now required to report on nature-related and climate-related disclosures, which can be very difficult to measure and track. This includes everything from water discharge into the ecosystem, down to proposed rehabilitation of any natural environment which is affected by a company’s operations.Broadening scope of measurement

In addition, it’s no longer sufficient for an organisation simply to report on its scope 1 and scope 2 emissions. Increasingly, scope 3 emissions are also required.Importance of accurate progress tracking

Organisations are also required to demonstrate their progress – with transition plans, target setting, forward-looking statements and plans. It’s no longer sufficient to provide lofty goals or a graph showing planned improvements. There is a growing need for organisations to develop and test detailed scenarios to accurately determine the steps they need to take – or how the business would respond if faced with a particular situation. For instance, how would the financial position of the organisation be affected if temperatures increased by 1.5° degrees? Or if there was a shortage of water?Growing role of data

Data is also playing an increasingly central role in enabling organisations to accurately track, analyse and report on climate and nature disclosures. Growing data volumes mean that organisations must have robust tools to perform effective analysis.Scope 1,2 and 3 in the context of mining and minerals

Scope 1

- Stationary combustion

- Mobile emissions

- Process emissions

- Fugitive emissions

Scope 2

Energy purchased

- Electricity

- Steam

- Heat

- Cooling

Emissions factors

- Location based method

- Regional or subnational emission factors

- National production emission factors

- Market-based method

Scope 3

Upstream

- Purchased goods and services

- Capital goods

- Fuel-and energy-related activities

- Upstream transportation and distribution

- Waste generated in operations

- Business travel

- Employee commuting

- Upstream leased assets

Downstream

- Downstream transportation and distribution

- Processing of sold products

- Use of sold products

- End-of-life treatment of sold products

- Downstream leased assets

- Franchises

- Investments

Climate & Nature

- Water

- Waste

- Recycling

- Air quality

- Soil pollutants

- Ecosystems

Figure 2: Scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions as well as Climate and Nature

As the table above demonstrates, scope 1 are essentially direct emissions. These are standard production outputs – for example, what you emit when you’re burning or combusting.

Scope 2 emissions are more indirect. This is about energy consumption.

For example, if you’re purchasing electricity, or using steam cooling.

Scope 3 is also an indirect, but it essentially includes everything else – even things like emissions associated with employee travel and waste recycling.

Nature and climate reporting is about the impacts on the surrounding environment.

So, is sustainability reporting really that difficult?

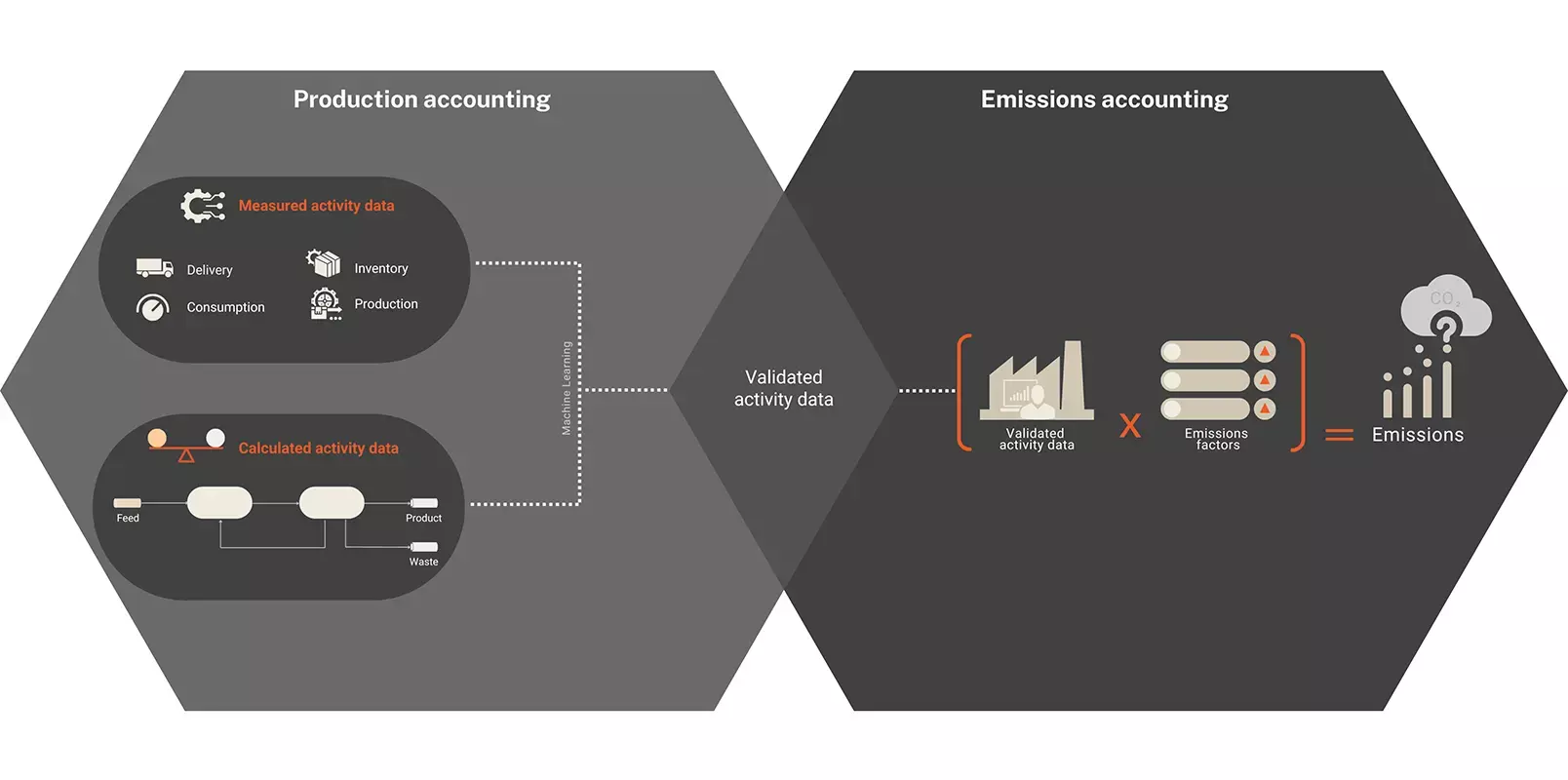

There is a strong link between sustainability reporting, financial reporting and production accounting.

As Metallurgical Systems, we often hear our customers say they find scope 3 reporting far too difficult.

The main reason for this is that organisations are still relying on error-prone, time-consuming manual processes and spreadsheets for their emissions reporting. Within the processing segment of the mining value chain, there is a very low uptake of systems that automatically consolidate relevant data and make it easily accessible in a transparent way. This needs to change. If you consider the fact that an average financial annual report has 87 pages (very time consuming to pull together manually), and that Australian regulatory bodies say they have identified over 8,000 errors in submissions since 2019, the case for corporate digital reporting is very clear.

It’s astonishing that Australia is still one of the few G20 countries where corporate digital reporting is still voluntary.

Scope 3 doesn’t have to be as difficult as people think

The above is an example of one of the dashboard reports we make available to our clients. As you can see, we clearly breakdown scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions, and reconcile this to hourly activity data. The organisation can also drill down into every single hour of every day of every week if required.

We also have validated activity data for site which may be under multiple jurisdictions – making it possible to very quickly pull required reports.

As engineers, it important that we actually report the actual data – and then we can let the accountants work out how they want to present it.

A lot of other systems will tend to use things like sales receipts and invoices and that’s one way of doing it, but it’s also somewhat flawed.

Let’s consider a potential scenario from a limestone plant. The plant is required to measure the amount of CO2 released per tonne of limestone used. Most regulators would measure this on a cost basis. So, if the plant purchases 100 tonnes of limestone, it is assumed that it releases approximately 44 tonnes of CO2. However, this mode of measurement has an obvious flaw: not all limestone is reactive. Even if 95% of the limestone reacts during production, the emissions are going to be significantly less than the system initially calculates.

There’s another problem too. If the plant is adding limestone to neutralise mild acidic solutions, the utilisation of the limestone drops significantly. This results in a situation where the plant’s emissions are overstated by 10%, 15% and potentially even 20%. This results in a real risk that the plant pays far more for its carbon offsets than it needs to.

To correctly measure the plant’s emissions, we need to look at the limestone which is consumed and how it is precipitated in granular detail. This calls for a solution with a mass and energy balance calculation.

The case for modern, digital tools for sustainability reporting

Put simply, without digital tools, the risk to your business is significant. The need for periodic reporting in a machine-readable digital taxonomy, scenario analysis and forward-looking statements means that data-driven technology is the only solution to meet evolving compliance standards. Manual spreadsheets simply cannot capture or process the volumes of data needed to deliver immutable, unalterable and auditable sustainability reports.

Ideally, resources organisations need a digital solution, using a dynamic simulation for a mass and energy balance, which can help:

- Simplify the tracking, reporting and management of emissions in granular detail.

- Get insights regarding their largest emitting activities and test alternative scenarios against accurate reduction targets.

- Create accurate budgets and forecasts.

- Track emission, energy and water consumption on an hourly basis.

- Create and test scenarios which reflect changes in process operations, to see what impact they will have on emissions (e.g., installing different equipment, altering throughput rates, or using alternative fuel).

- Capture data in keeping with all relevant global standards.

Reporting standards are now mandatory in many jurisdictions, with financial penalties for noncompliance. The requirements are also growing and intensifying – and organisations need to act now. Digital solutions will enable us to meet our obligations and improve outcomes. Accurate transparent reporting is the key to ensuring evidence-based decision making.

To learn more about current regulatory requirements and how a digital solution using a dynamic simulation mass and energy balance for accurate and auditable sustainability reporting can help, contact our expert team on +61 2 7229 5646 or info@metallurgicalsystems.com

About the authors

This article has been collaboratively authored by the team at Metallurgical Systems, and fact-checked and authorised by Managing Director and industry specialist John Vagenas.